When Melbourne-based researcher, teacher, writer and poet Dr Yusef Sheikh Omar shunned traditional Somali naming traditions to name his newborn baby Amelia, his decision was met with intense disappointment and anger by the older members of the Somali-Australian community. They felt that it was a betrayal of their Somali and Muslim identity.

Having extensively researched the challenges of social integration into Australian and US society for refugee youths of Somali background for his PhD, Omar and his wife Khadijo settled on Amelia because they felt that would help with becoming an ‘Aussie’. But he was aware that his defence that ‘Names are neutral’ was open to challenge. A name defines and shapes a person and conditions the ways others form impressions about them. Often it tells a story of their social or ancestral background. Fairfax newspapers recently published a piece by Omar about his difficulty in naming their daughter.

Some people are named after a grandparent or other relatives, or even national events or celebrities. In early May, royal-watchers celebrated the arrival and name announcement of Her Royal Highness Princess Charlotte Elizabeth Diana of Cambridge. The royal tradition of choosing names after relatives (in this case, grandfather, great grandmother and grandmother) lives on in the UK – a fact that did not escape the betting public who collectively won more than ₤1m backing Charlotte as the second favourite.

As a society, we find meaning in names. In Somali culture many children are named after environmental or circumstantial events such as Geedi (born during travel) or Ubax (born whilst surrounded by aromatic flowers. Others are named after desirable personal traits with boys’ names such as Arale (Clean), Awaale (Lucky), Burhaan (Charisma), Guleed (Victorious) and Samakab (Supporter of right); and girls’ names such as Awrala (Without blemish), Fathia (Opener of fortune), Magol (Early flowering) and Sagar (Morning star).

People from the Horn of Africa often comment with amusement on the contrasting impersonal or occupational nature of many Anglo-Saxon family names such as Smith, Brown, Turner, Wall and Hill.

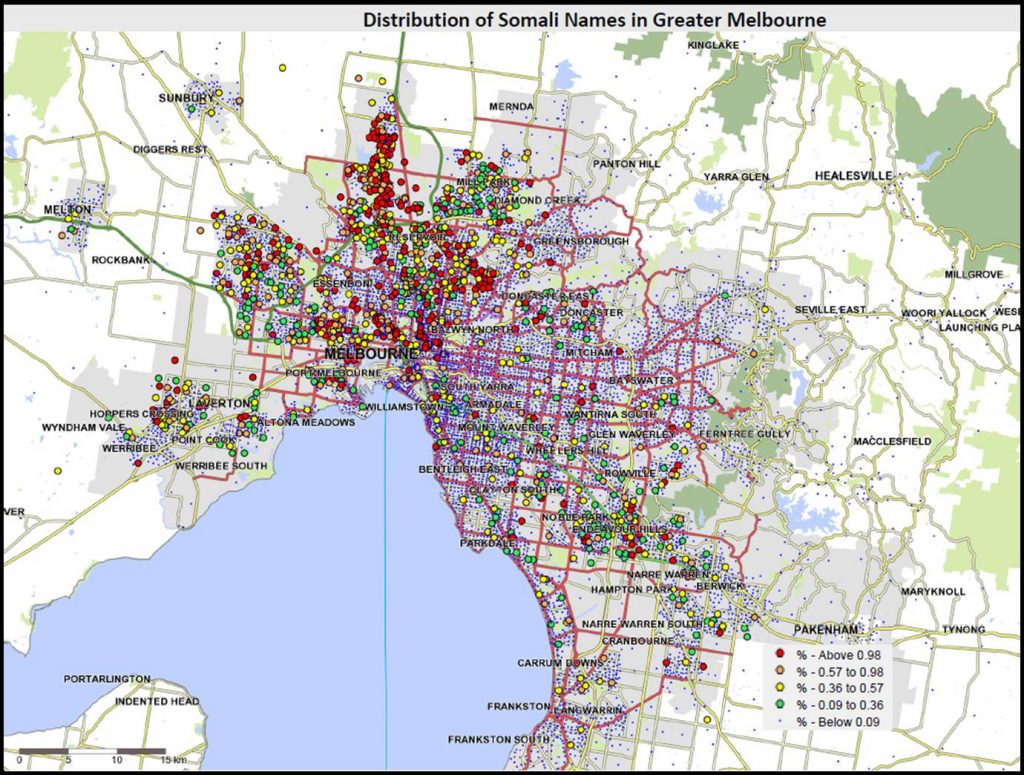

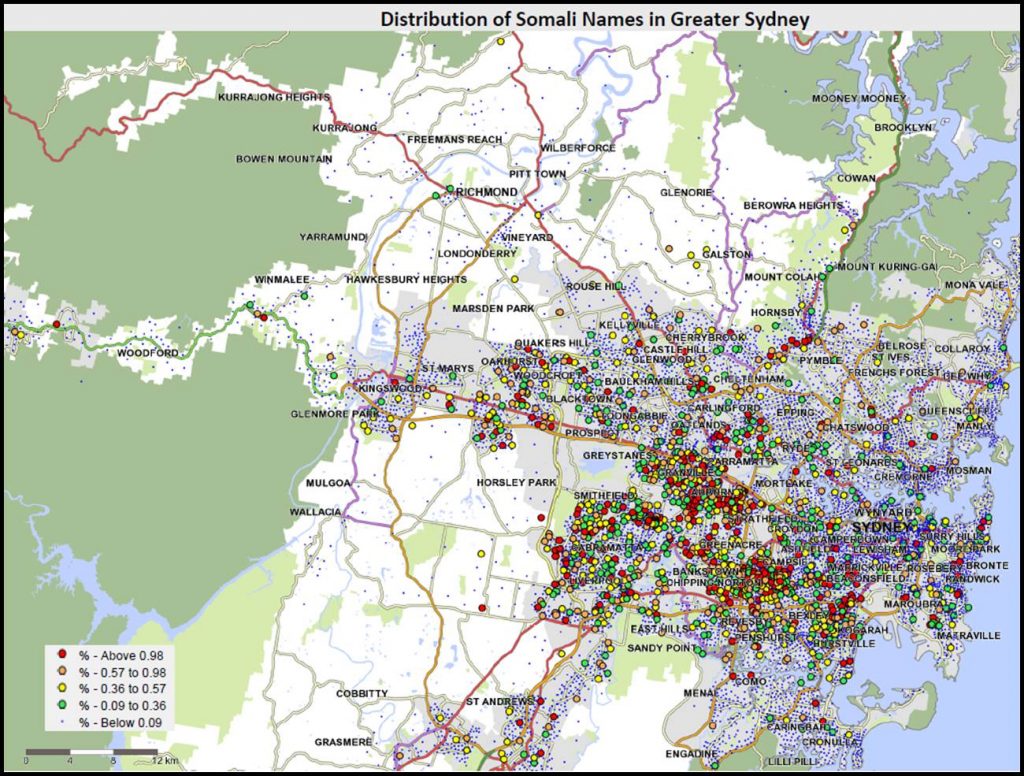

In the Origins database, we identify more than 8,000 individuals with Somali names. Some of the most common family names include Younan, Abboud and Khamis. As is often the case, refugee and migrant communities often co-locate. This is partly a response to the housing market and public transport availability. But it is also because of the attraction of nearby support from friends and relatives or to take advantage of culturally-specific economic and community facilities, such as specialist retailers and social clubs.

In Melbourne, most of the Somali population is located in the northern suburbs, with particular concentrations around Roxburgh Park, Craigieburn, Heidelberg, Carlton and Footscray, and secondary centres around Dandenong, Hoppers Crossing and King’s Park.

In Sydney, the preferred locations are Parramatta, Auburn, Lakemba and Rockdale with additional concentrations around Erskine Park, Smithfield, Mount Pritchard and Thornleigh in the north.

Every parent consciously chooses a name and many will balance the weight of tradition with visions for the future. In response to Somali community disapproval, Omar and Khadijo diplomatically compromised and used the name Eemaan (Faith). But many young people still call her Amelia.

With all of Australia’s diverse communities, Origins is a highly effective predictor of cultural background and gender and a useful guide to language preference and likely religious inclination. Drawing on extensive name and geographic research, Origins can help you uncover the cultural dimensions of customers and their behaviour. Contact OriginsInfo to find out more about how you can reveal these valuable insights about your customers and better meet their needs.

Back to blog